There are many different things that can affect resins ability to cure properly and understanding how and why this happens can help you have more successful casts. This post will cover a range of these things so that you can avoid common pitfalls and troubleshoot where any failed casts went wrong. This guide is mostly aimed at mixing and curing clear resins, but many of the points will also be helpful for other types too.

Mixing the resin

One of the most common reasons for resin to not cure properly is under-mixing. Many of the instructions sheets that come with resin just say to mix the resin for x amount of time and leave it at that. While that might be sufficient in some cases, there’s usually more factors to consider to get a properly cured cast.

The first thing to consider is what you’re using to mix with. The surface area of your mixing tool is very important as mixing with something small will give very different results from mixing with something with a nice large flat surface, as a larger surface moves the resin around more. My favourite thing to mix with is a mini baking spatula, but it will depend on the amount of resin you’re working with as to what will be best for you. The main thing to avoid mixing with is anything porous (e.g. popsicle sticks) if bubbles are a concern, as air can leech from it into the resin. Anything plastic or silicone based with a large flat surface will work well.

Once you have your tools ready, the next thing is to make sure you get the right ratio of resin to hardener. Different resins use different methods for achieving this- for epoxy or urethane resins this can either be by weight or by volume and it’s important to know which method is used for your particular resin, as otherwise the ratio will be off. If you’re mixing by weight the scales need to be sensitive enough for the amount of resin you’re mixing (e.g. bathroom scales wouldn’t be good for mixing small amounts). The more sensitive the scale the closer you can get to the correct ratio. However, it also needs to go high enough for the amount of resin you want to mix as scales have a maximum weight cut off. Many scales will state what both of these are on them so that you can choose the right one for your project.

The other thing that could put the ratio off is if you mix less than the minimum pour amount for your resin. With resin being fairly pricey it can be tempting to mix a tiny amount if you don’t need much for your current project, but if it’s less than the minimum it’s much more likely that the ratio will be too far off to achieve a proper cure. For example, let’s say we were trying to pour 10g total of a resin that’s mixed 1:1, but accidentally under poured the hardener by 1g. This would put the hardener amount off by 20%. However, if we were pouring 20g of resin we would only be off by 10%. The less that’s poured, the more exact the measurements have to be. Each resin is different as to how much it can tolerate being off the ratio, but for very small amounts it may not be possible to get it close enough. The other factor is that there may not be enough heat in very small amounts for the resin to cure even if the ratios were exact. Some companies will specify a minimum mix amount, but not always. In general, if you’re only mixing a few tablespoons worth it’s likely to cause problems. The minimum I try to stick to is 12g, but that’s with a heat mat for curing so it may be different for your setup.

Once you have the ratios worked out and have poured the resin and hardener, the next thing to do is begin mixing. You’ll notice that the resin will start to go cloudy and streaky- this is a good way to tell how mixed it is. When the resin’s fully mixed it should look completely clear again- if there’s any streaks it indicates that there’s unmixed hardener still. While you’re mixing it’s a good idea to scrape the sides and bottom of the cup to dislodge any hardener that gets stuck on the surfaces. Once the resin looks totally clear it’s important to then ‘double mix’ it by getting a new, clean cup, pouring the resin into it, and mixing again for a short time. This will leave behind any hardener still stuck on the sides, as scraping won’t usually get all of it. As you pour aim to transfer just the bulk of the resin and don’t wait for the rest to drip out as it’s more likely to not be fully mixed. I also like to wipe off my stirring implement before mixing again so that I know there’s no hardener sticking to that either.

Cure inhibition

Resin mixing can be a big factor as to how well it cures but there are other pitfalls to watch out for too. One of the great things about clear resin is using different inclusions and colourants to make interesting pieces, but not everything will play nicely with resin. Water is one of the most common problems as it’s found in so many art supplies and can greatly affect how well resin cures. You can sometimes get away with a tiny amount of water if you’re careful, for example some people use a small amount of acrylic paint to colour epoxy. In general though, it’s best to avoid water based products where possible. Another commonly used colourant is alcohol inks as they can give great translucent colours, but these should be used sparingly as isopropyl alcohol will also inhibit resin’s ability to cure (but to a lesser extent than water will). Some better colourants to use include mica or other powders for an opaque look or quality resin dyes for translucent (avoid those big packs of ‘resin dyes’ you can get for cheap as they often inhibit the cure worse than alcohol ink).

Another thing that can inhibit resin is certain silicone moulds. There are two main types of silicone used for moulds- tin/condensation cure and platinum/addition cure. Tin cure silicones are less easily inhibited themselves when making the mould, but more likely to cause resin to not cure right, while platinum silicones are easily inhibited by sulfur, but won’t cause any issues with resin curing. There are many reports of tin cure silicone causing resin to not cure on the parts touching the mould, leaving a sticky outer layer. A couple of common problematic ones are Alumilite amazing mold rubber and Oomoo series silicones. It’s common for people to buy these ones as they’re slightly cheaper than platinum cure options, but its worth the extra cost to ensure a good cast.

The last thing that can inhibit resin from curing is the age of the resin itself. Resin has a shelf life, so only lasts so long before it starts to degrade in quality. You can usually tell when this is happening as the hardener starts to yellow significantly. Using old resin can still work and the yellowing can be disguised with colourants, but there’s no guarantee that it’ll cure quite right. If you’ve controlled for other factors and are still having trouble, you may have better luck with a fresh batch instead.

Curing Environment

The last major thing that can affect resin curing is the environment in which it cures. The main factors that can affect it at this point are the humidity and ambient temperature. If the humidity is too high it can cause either the whole cast to go cloudy or just the surface exposed to air (called amine blush). Working in a climate controlled environment can help mitigate this, or even just checking the weather and not casting on days where the humidity is high. For people working with pressure pots it can also be helpful to install a moisture trap as part of your setup.

For the temperature, it’s important not to leave resin to cure anywhere that’s too cold. Resin hardens via exothermic reaction and if it’s left somewhere cold it won’t be able to generate enough heat to cure properly. Most resins will have a suggested ambient temperature that it’s best to cure at, or if you want to ensure a good cure an external heat source can help it along. Heat boxes are a common solution, they can be made from a heat lamp or warm lightbulb in a box lined with something reflective, or I like to use a cheap pet or seedling heat mat in a sealed plastic box (it also keeps the fumes in that way). Some more serious people will even use an oven set on low to help them reach full cure faster (this has to be a dedicated craft oven though and can never be used for food again). Basically any source of low heat in a container will work so you can be creative, I’ve seen one person using a reptile incubation machine to achieve this. It’s important to only use a low heat as too much can cause a runaway exothermic reaction, which can be dangerous and will ruin the piece.

This guide covers a lot of points, but resin can be pretty forgiving so it’s worth just giving it a go and trying out these tips over time. You can definitely get a reasonable cast from cheap moulds and without investing in things like heat mats in the beginning. If you have any other suggestions that I’ve missed feel free to leave a comment down below.

Final useful tips

-If you’ve controlled for humidity but are still getting what looks like amine blush on your pieces, it can also be caused by some colourants or under-mixing of very finicky resins (even with double mixing)

-If you’re having curing issues that you can’t pinpoint make sure you’re not mixing with anything that could leech chemicals into the resin. I’ve seen some people mention that something in the popsicle sticks they used prevented their resin from curing, or also the wax coating from paper cups

-Make sure not to mix too much resin at once or leave it for too long if you’re using a medium to fast curing resin. When the resin is in your cup it can often be above the recommended pour depth and in some cases cause your cup to melt

-You should never have to significantly adjust the amount of hardener from the recommended amount. If you’re having curing issues troubleshoot what could be causing them, adding more hardener will just make it harder to figure out the issue and get good casts

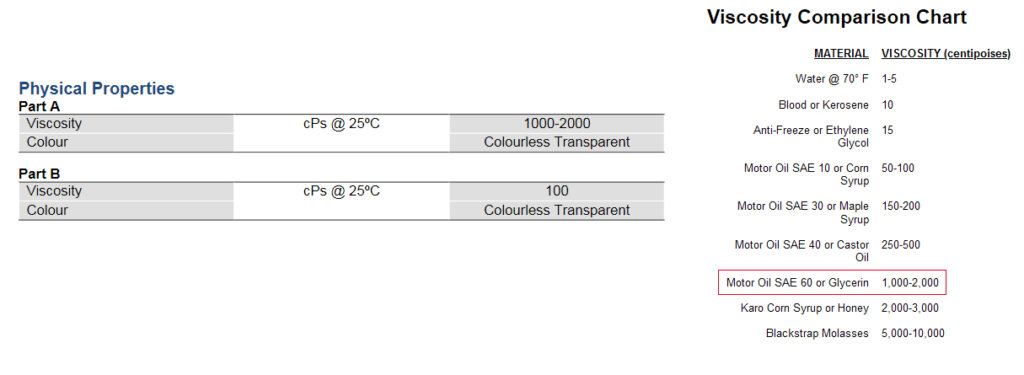

-It can be easier to mix your resin if you first heat the resin bottle it in a warm water bath prior to starting. This lowers the viscosity, making it easier to mix the two parts together (but will also reduce the pot time)

-If you have a pressure pot/vacuum chamber, or are using a very slow setting resin you can also use something mechanical to mix your resin easier. Small paddles connected to a drill are a common option. It’s more likely to add air this way though which is why it’s only recommended in those circumstances